While

investigating the life of Barnabas Horton, I purposely limited my time

examining scientific evidence such as genetic testing. I was new to the field

and information at that time caused more confusion than clarity. Now, however, it’s

time to discuss this important, parallel track of genealogical inquiry—YDNA

testing and its impact on known Horton family lines.

In

a recent issue of its quarterly magazine, American

Ancestors, the New England Historic Genealogical Society published an

article summarizing important findings of the Horton Surname

Project

hosted at FamilyTreeDNA.com. I’m grateful to NEHGS for granting me permission

to upload the article permanently on my website. You can find it at Resources tab at the top of the webpage,

then under Books and Articles. The

NEHGS article and this blog should be read together as companion pieces.

The

Horton Surname Project seeks to determine possible connections among various

Horton lineages in the U.S. and U.K. The best way to do this is by comparing

YDNA samples from men whose surname is Horton (along with some spelling

variations), since YDNA is passed from father to son. My husband submitted his

YDNA in 2012 along with a written summary of his Horton lineage as he knew it,

ending with Barnabas Horton of Southold.

I

soon learned from project administrators, that test samples from men who

self-described as descendants of Barnabas fell into two distinct groups not one,

as expected. The surname project had samples from males who descended from

Barnabas’s son Joseph and from males who descended from Barnabas’s son Caleb. You

could think of these groups as Team

Joseph and Team Caleb. In the

future, there could also Team Joshua

and Team Jonathan as descendants of

those lines submit samples, but never Team

Benjamin because he died childless.

My

husband was assigned to Team Caleb.

Project

administrators noticed some unusual groupings. YDNA from Team Caleb matched samples from men whose oldest known ancestor was

a Quaker named Abraham Horton, born in Pennsylvania around 1720. Team Caleb also matched YDNA from men

with surnames other than Horton, such as Johnson and Curtis, all of whom had

southern lineages. In an attempt to find where these genetic breaks occurred,

project administrators actively recruited test samples from descendants of

other lines. Eventually, YDNA was secured from three previously untested teams—Team Jonathan, a new subset of Team Caleb, and Team UK.

Although

the meaning of Team Jonathan should

be clear, the two others not so much. Try thinking of it this way: My husband

was on Team Caleb via Caleb’s son

Richard. The new participant was on Team

Caleb via Caleb’s son Elijah. And Team

UK was just as implied. A British national named Horton whose line traced

back to late-seventeenth century Mowsley, agreed to have his YDNA tested. A

first for the project.

I

won’t keep you in suspense. Team Jonathan’s

sample matched those of Team Joseph.

The sample from Team Caleb via Elijah

matched those of Team Joseph, but did

not match my husband’s sample, Team Caleb

via Richard. And Team UK’s sample

matched those of Teams Joseph, Jonathan, and Caleb via Elijah, but not

the sample from Team Caleb via Richard.

My husband’s team had struck out. Science proved he and others on the same team

had no genetic connection to Barnabas Horton of Southold. Instead, Team Caleb via Richard descended from a

Pennsylvania Quaker of unknown origins!

So

how did this incorrect family assignment

occur? Perhaps in a rush to align their families with Southold’s local hero,

Barnabas Horton the Immigrant, early 19th-century researchers

presumed kinship ties based on identical surnames, proximate locations, and the

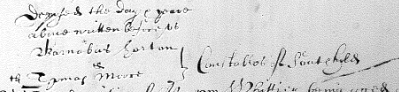

inevitability of westward migration. Roxbury Township, New Jersey was formed in

1740, eight years before Caleb Horton (Barnabas3, Caleb2,

Barnabas1) arrived from Southold, Long Island, with his family. His 1759

last Will & Testament made no mention of a son named Richard, but did name

a son Elijah. A 1768 codicil to that Will also made no mention of a son named

Richard, but again named Elijah. Finally, the Salmon Papers made no mention of Richard’s birth in Southold nor his

marriage to Elizabeth Harrison.[1] The earliest records made

by Richard Horton of southeastern Pennsylvania are from the late 1760s, creating

a twenty-year gap from when Richard allegedly arrived in New Jersey to when he

was taxed in Pennsylvania. The absence of paper evidence mirrors the lack of

scientific evidence.

An

objective researcher would have to acknowledge that the documentary evidence cited

above concerning Richard’s relationship to Caleb Horton of Roxbury, faltered

under close scrutiny and collapsed under the weight of scientific evidence. As

a dedicated biographer, I appreciate what a big let-down this is for my family

and will be for hundreds of descendants on Team

Caleb via Richard. Yet, it’s not unheard of in the age of genetic genealogy.

Buck up, Team Caleb via Richard! I’m

open to receiving primary evidence about Richard Horton and/or Elizabeth

Harrison, but please—no references to George Alloway’s book. He cites no

concrete evidence. Descendants on this line must consider an unfamiliar path

towards discovering their family’s new Immigrant Ancestor.

I

haven’t given up on the ultimate challenge however—identifying the parents of

Barnabas Horton of Southold. Earlier this summer, I spent a week at the

Leicestershire record office tracking down clues and indirect evidence

discussed in the book. I don’t know yet if there will be enough material for a

second edition of In Search of Barnabas

Horton, but perhaps a stand-alone expansion of Chapter One. Stay tuned.

[1] The Salmon Papers was a private account of marriages and deaths in

Southold. I should note that it missed many events, not just Richard’s

marriage. Interested readers are directed to a detailed treatise on the Horton

family of Roxbury, New Jersey written and posted by Terry Harmon at

GenForum.com, entitled “Caleb & Phebe Terry Horton Family Theories,” dated

July 12, 2011.