Over the

course of writing this book, I spent a lot of time pondering whether or not

Barnabas knew how to write, including penning his own name. I knew it wouldn’t change

my opinion of him. He would remain a resourceful and pragmatic tradesman with

or without this particular skill. Curiosity drove me. Several people pointed out that his signature

regularly appeared in Southold’s town record books. What better reason to sit

at a microfilm reader at the Southold Free Library for hours?[1]

After reading and comparing dozens of pages, I concluded that Barnabas took

oral depositions which were then recorded by the town clerk. A dead

end.

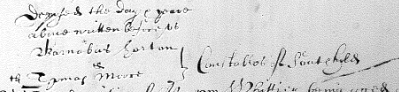

I then considered probate documents and came across another Barnabas "signature." This time as one of five witnesses to Thomas Terry's will, written in 1671. Inconclusive again. The signatures I kept finding were too dissimilar to have been written by the same man, even across time.

|

| A portion of Thomas Terry's will, New York Public Library. |

The only original document guaranteed to have his personal signature or mark would be Barnabas's own last will and testament. Did it still exist? The search was on.

In late fall

of 2014 while randomly googling on my computer, I came across an image of a blueish,

carbon copy of a typed transcription of Barnabas’s will. A handwritten note in

the margin said the transcription was made by the last known owner of the

document.[2]

Several mouse clicks later, I had the names and addresses of the owner’s last

known family members. I carefully crafted a letter explaining my book and

interest in Barnabas’s will. I dropped the letters in the corner mailbox with

the expectations of someone flinging a message in a bottle into the vast ocean.

How long would it take to get a response—if ever? How on earth did genealogists accomplish as much as they did before the internet?

I heard back

within a month. My postal inquiry had triggered an exchange of emails among the

four children of the will’s last owner—Peg (97), Allan (93), Alice (90), and

Betty (87). The older siblings remembered the will while the younger ones did

not, yet they all agreed that the treasured document was likely put in

safekeeping at the family’s summer retreat in northern New Hamphsire. What an

exciting addition to Barnabas’s biography! When could I see it? Mindful of my

impending publication date, the siblings tried to brainstorm a solution, but access

to the house was already blocked by deep snow and would remain impenetrable until

the spring thaw. I knew I couldn’t rewrite the text and related footnote without

significantly altering page numbers which would, in turn, delay publication and

increase my expenses. With mixed emotions, I decided that any information revealed

by the will would have to wait for a second edition.

I made two

trips to New Hampshire in the summer of 2015, after the book’s publication. The

first trip included a lively lunch with Allan and Betty, swapping stories and

Barnabas lore. The second was to their family homestead for a viewing of the

will. I missed meeting Peg, but Alice and her family were wonderful hosts, and

graciously allowed me to take lots of photos to share with Horton cousins everywhere. (Once again, I'd like to express my thanks to Peg, Allan, Alice, Betty and their families!)

The will is

beautiful. Cramped text fills one side of parchment. It's smaller than the two copies I had previously come across.[3]

It appears to have been framed in the early 20th century by a professional

archivist and is stored in a closet away from any light source, perhaps an

added layer of preservation in the days before UV-filter glass. A reverse-negative facsimile was created and placed on the protective cover. The text reads

like the copy entered into the Suffolk County court minute book at

Riverhead, NY.